The Saddle Point Approximation

As we stated in the last section, the types of transformations and reference hypotheses

for which analytic expressions are available are limited.

For a broader class of statistics,

the exact moment generating function (MGF) is often known.

The problem is that inversion of the MGF transformation to find the exact PDF

may not be possible in closed form. For these cases, we

can use the saddle point approximation (SPA) which provides accurate

tail PDF estimates. Steven Kay was the first to recommend the

saddle point Approximation as a solution to this problem in CSM.

Later, it was futher developed by Nuttall [16].

It should be kept in mind that although the SPA

is an approximation, approximation errors can be ignored for all

practical purposes [1].

Furthermore, the accuracy is not degraded in the PDF tails.

On the contrary, it is extremely well adapted to the task at hand, even for

input data very far from the central peak of the reference hypothesis PDF.

This is because the SPA approximates the

shape of the integrand, not the value (height) of it.

There are limits, however

and we find that the SPA, which is a recursive search for the

saddle point itself, may suffer from convergence problems.

This problem is solved using the data normalization, which is a special case

of a floating reference hypothesis and is described in section 2.3.4.

Further details about the SPA are provided in Appendix 17.6.

Let feature

.

The moment-generating function for

.

The moment-generating function for

is given by

is given by

for  -dimensional Laplace transform variable

-dimensional Laplace transform variable

.

Then,

.

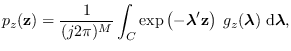

Then,  is obtained by the inverse Laplace transform:

is obtained by the inverse Laplace transform:

where

The contour

The contour  is parallel to the imaginary axis in each of the

is parallel to the imaginary axis in each of the  dimensions of

dimensions of

.

The joint cumulant generating function (CGF) is

.

The joint cumulant generating function (CGF) is

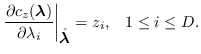

For a specified  , the saddle point is that real point

, the saddle point is that real point

where all

where all  partial derivatives satisfy

partial derivatives satisfy

The saddle point may be found iteratively using the recursion

where

is the gradient vector of

is the gradient vector of

w/r to

w/r to

, and

, and

is the

is the  matrix

of second partial derivatives

matrix

of second partial derivatives

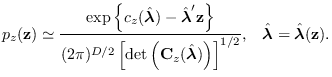

Once the saddle point

is found,

the saddle point approximation is given by

is found,

the saddle point approximation is given by

|

(2.12) |

Example 2

Let  be a set of

be a set of  samples of positive-valued

data, such as intensity or power spectrum measurements.

Let

samples of positive-valued

data, such as intensity or power spectrum measurements.

Let

, where

matrix

, where

matrix  is

is  .

This is a simple linear operation producing the

.

This is a simple linear operation producing the

-dimensional feature

-dimensional feature  .

To compute the J-function for this

feature transformation, we need to select

a reference hypothesis

.

To compute the J-function for this

feature transformation, we need to select

a reference hypothesis

for which we can compute

the feature PDF

for which we can compute

the feature PDF

.

We are tempted to use the Gaussian PDF

since the Gaussian PDF of

.

We are tempted to use the Gaussian PDF

since the Gaussian PDF of  would be trivial to derive.

Although (2.2) would result in a valid projected PDF,

would be trivial to derive.

Although (2.2) would result in a valid projected PDF,

would have support for negative

values of

would have support for negative

values of  , which would violate our prior knowledge

that

, which would violate our prior knowledge

that  was positive. Other reasons why this is a bad choice

of

was positive. Other reasons why this is a bad choice

of  are discussed on chapter 3.

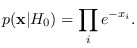

A much better choice is the exponential PDF

(1/2 times the standard

are discussed on chapter 3.

A much better choice is the exponential PDF

(1/2 times the standard  random variable

: chi-square distribution with 2 degrees of freedom, scaled by 0.5)

random variable

: chi-square distribution with 2 degrees of freedom, scaled by 0.5)

Unfortunately, the PDF

is not known in closed

form. This problem was adressed in

2000 by Steven Kay who suggested the use of the saddle point approximation

(SPA) [16].

Although

is not known in closed

form. This problem was adressed in

2000 by Steven Kay who suggested the use of the saddle point approximation

(SPA) [16].

Although

is not known in closed

form, the moment generating function (MGF) is known.

Is is just a matter of numerical inversion of the MGF.

We address this problem in detail in Section 17.6.

The function software/pdf_A_chisq_m.m implements

the algorithm that computes

is not known in closed

form, the moment generating function (MGF) is known.

Is is just a matter of numerical inversion of the MGF.

We address this problem in detail in Section 17.6.

The function software/pdf_A_chisq_m.m implements

the algorithm that computes

.

.

To test the approach, we generated data  as

as  independent samples of from the

independent samples of from the  distribution,

for

distribution,

for  , then used the matrix

, then used the matrix

We compared the histogram of the values of  with the

SPA for each histogram bin. Figure 2.2 shows the result.

with the

SPA for each histogram bin. Figure 2.2 shows the result.

Figure 2.2:

Comparing histogram with PDF approximated using SPA.

|

|

The saddle point approximation is used in many examples in this book.

These examples include

sections 17.6, 17.7.1, 9.1.2, 2.3.2,

and 5.2.1.

![]() .

The moment-generating function for

.

The moment-generating function for

![]() is given by

is given by

![$\displaystyle {\bf C}_z(\lambda) \stackrel{\mbox{\tiny $\Delta$}}{=}\left[ \frac{\partial^2c_z(\lambda)}{\partial \lambda_l \partial \lambda_m}\right].$](img172.png)

![]() is found,

the saddle point approximation is given by

is found,

the saddle point approximation is given by

![]() as

as ![]() independent samples of from the

independent samples of from the ![]() distribution,

for

distribution,

for ![]() , then used the matrix

, then used the matrix

![$\displaystyle {\bf A}=\left[ \begin{array}{ll} 1 & 0\\

1 & 1\\

1 & 2\\

1 & 3\\

\vdots & \vdots \\

1 & N-1

\end{array}\right]

$](img178.png)